Welcome back, hummingbirds! I always feel lucky spotting the first ruby-throated hummers to grace my porch each spring. Although, to be honest, I can’t initially tell if I have two new Best Bird Friends™ or it’s just the same bird fueling up over and over again. Attracting hummingbirds is a relatively easy and enjoyable way to interact with nature; they’re mischievous and territorial little flyers capable of amazing acrobatic stunts just to compete for a sip of that good, good sugar water. Here’s a few ways you can best serve the hummingbirds that visit your home should you decide to attract a few.

✔️ Do: Purchase a hummingbird feeder that’s easy to clean

Unlike seed feeders for songbirds, hummingbird feeders need regular cleaning to keep bacteria growth at bay. When left too long in the heat, sugar nectar can grow some gnarly slime and grime. Feeders should be rinsed with warm water every three days — this often syncs with how often the birds need a refill. And come summer, it can be a more time consuming job of every day to every other day, since hot temperatures are like a bioreactor for bacteria. You’ll find tons of plastic feeders out there on the cheap, but I recommend finding a glass option. They’re sturdier, easier to clean, and last longer.

Pro tip: I buy new feeders on clearance at the end of summer to save a few bucks.

✔️ Do: Make your own hummingbird nectar mix

There’s nothing special about hummingbird food from big box stores. You can make your own at home by dissolving 1/4 cup of white granulated sugar in 1 cup of hot water. (The magic ratio is 1:4, so expand your batch as needed using this formula.) Let it cool before adding to your feeder, and store any extra in the fridge for use later in the week.

❌ Don’t: Add food dye to your hummingbird nectar

Some commercial nectars use red dyes to attract hummingbirds, though it’s not necessary (that red dye 40 may actually be harmful to birds). The Audubon Society recommends steering clear of store-bought nectars that use red food dyes. Skip the red food coloring at home, too.

❌ Don’t: Fret if the hummers are hesitant

They may not be in your area yet. Hummingbirds slowly spread throughout the country between late March and early May, with males arriving first and females a week or two later. You can encourage them to pit stop at your feeder by making the surrounding area more attractive with eye-catching red flowering plants (bonus points for selecting native species that cater to multiple creatures in your environment). With a lifespan of 3 to 5 years, hummingbirds often return season after season to spots where they last found food, so if you had successful feeders up last year, you’ll want to put them back in the same location.

❌ Don’t: Panic about avian flu

H5N1 is a big deal in the news right now, and I got to wondering if it’s transmissible to hummingbirds. It appears hummingbirds have a reduced risk of catching avian flu based on their feeding and behavior habits, though there’s not much research on them specifically. As of April 2025, Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology advices that wild songbirds and “typical feeder visitors” have a low risk of catching the disease, and while hummingbirds aren’t specifically mentioned, I haven’t yet found advice that treats them differently. Still, extra vigilance doesn’t hurt: remember to clean feeders and birdbaths regularly, and wash your hands after interacting with those items.

✔️ Do: Make some new friends

Research shows hummingbirds have incredibly sharp memories and may be capable of remembering human faces. So if you end up bonding with these tiny flying baddies, there’s a good chance you could see them again and again, and even next year. 🪺

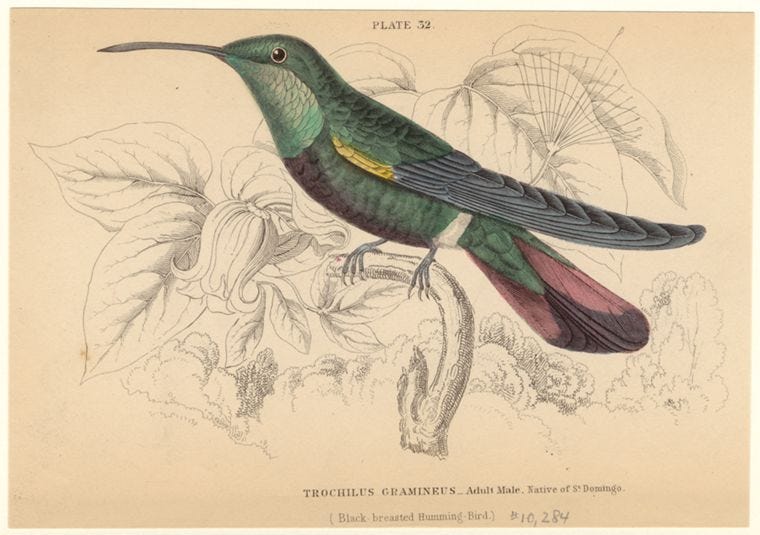

Art note: “Trochilus gramineus (black-breasted humming-bird)”, depicted in the 1852 edition of The Naturalist’s Library: Containing scientific and popular descriptions of man, quadrupeds, birds, fishes, reptiles and insects, according to the classifications of Stark.