In this month’s issue:

A guide to getting your feet wet on hot summer days, no pool pass required

How to get lit after dark with a bunch of furry, flying friends

A recipe for using berries you can forage this month

Sorry to break it to you, but lightning bugs have not-so-innocent underground lives

Plus a few other nature notes.

Hello, friends!

Summer’s arrival this month has sparked a little retrospection, namely about my childhood summers. One of my favorite things as a girl of the Y2K era was creating sparkling, ornate summer bucket lists with the hoard of neon gel pens my teachers banned during the school year (something about the glitter being supposedly illegible). Making these lists felt like the surefire way to squeeze every last sunshiney drop out of summer before school started up again in August.

Gelly Roll pens and summers past have faded away, and I’m no longer 12. Somehow (???) I’m a mom with my own kids home for the summer. I’ve been thinking back to how I once made those lists, using them as inspiration to conjure up a little summer magic à la the late ‘90s and early ‘00s. You know, running through sprinklers, campouts, bike rides and crashes (maybe not the stitches part), and no iPads. It’s occurred to me that the summer bucket list is in dire need of a return, but not just for my kids. I’m nostalgic for summer days filled with promise and fewer cares, where time exploring was well-spent, and the strain of living in this chaotic and calloused world hadn’t yet found me.

June is the start of a new month and season, and research shows that diving into a new project or goal when we have a self- or seasonally imposed fresh start can trick our brains into accomplishment. This month, I challenge you to draft your own summer bucket list before the season gets underway. The assignment is easy: jot down things you want to do just because, and tackle them spontaneously as the hazy days of summer allow. Just make sure a few items include time spent outside, especially during Great Outdoors Month in June.

(P.S. My modern pen of choice is the Pilot G2. Heavily pigmented gel in a rainbow of hues, just a bit more legible.)

This month, outdoors

A few ideas of how you can enjoy what nature has scheduled for June

🦋 Summer Mothin’, Had Me a Blast

Butterflies may be the harbingers of spring, but hot summer nights belong to the moths… and there are a lot of them. Moths outnumber their daytime counterparts 8 species to 1 (some estimates push this as high as 10:1). While both sets of delicate pollinators belong to the Lepidoptera classification, much more separates them than their daily schedules. There are a host of anatomical differences, from colors and antennae features, to how wings are held while at rest. June is the perfect time to observe some of these differences up close, and give moths a little more respect. Get out those old sheets you planned on donating but never actually dropped off at Goodwill, because we’re going mothing.

My first mothing experience in 2022 was with experienced enthusiasts, though you don’t need a guide or Ph.D. to try it. Mothing (aka “lightsheeting”) is really just attracting nighttime insects for observation. It takes only a few tools — a light source, a white or light-colored sheet, and patience.

Step 1: Find your mothing location

The goal of lightsheeting is to attract these nocturnal insects to you, not some random porch light. Look for a dark area away from artificial lights to cut down the competition and attract your new fuzzy-antennaed friends.

Step 2: Hang your sheet

That old sheet is about to serve as your moth landing zone. It should hang vertically so moths can approach easily. Create a clothesline between two trees or objects and pin your sheet up, or tack it sheet to the side of your fence or house (it’s easier to observe moths at eye level). And a word of wisdom: This step is most easily accomplished before dark.

Step 3: Add a bright light

Moths are (obviously) attracted to bright lights, and you’re about to give them exactly what they want. Set up your light in front of the sheet, aiming it to illuminate the landing zone. Any type of light will work, though mothing experts recommend using a blacklight if you have one to attract a larger variety of insects.

Step 3: Wait and watch

The hardest part of moth watching (so long as you did all the setup in the daytime!) is the wait. As the night goes on, more moths should find your observation area, and that’s where the fun really begins. The brightly lit background makes it easier to photograph your new mothy BFFs so that you can identify them once you’re back indoors. A few of the apps and tricks I recommended for wildflower identification last month also work for moths and butterflies!

Half the appeal of mothing is that it’s simple. How hard you deep-dive into your moth musings, or how long you hang out, depends on your level of interest. I recommend keeping your first lightsheeting attempt low-key — sit back with a beer and enjoy meeting all the pollinators who party long after you’ve normally gone to bed.

🦋

🏖 A Little Non-Chlorinated Fun

Pool season in the Midwest is off to a rocky start this summer. Turns out, periodical cicadas can wreak havoc on pool filtering systems, causing clogs and requiring hours of work to clear them all away. And if it’s not bugs, it’s the deluge of storms that keep battering the Midwest in what feels like the wettest start to summer in recent memory. Planning a pool day has been touch-and-go so far; who wants to pay entrance fees just to get called out of the water when another thunderstorm rolls in? Luckily, my favorite way to cool off involves a little summertime magic: the good old-fashioned creek walk.

Creekwalking is exactly what it sounds like: walking through a creek on a hot day. But with a little imagination, it’s essentially a water safari. Walking through shallow waters presents the opportunity to slowly explore underwater ecosystems teeming with life. My preferred hangout spots have a little current to keep things moving but rarely surpass knee-depth; being able to see the creek bottom is a large part of the adventure.

What to wear: Creekwalking doesn’t require any special gear, though I recommend wearing water shoes or old sneakers to protect your feet and provide traction on slippery surfaces. Swimsuits aren’t required, though I often wear one because creekwalking tends to become creeksitting and relaxing.

What to pack: You don’t need much. Because I’m normally toting two kids along for an afternoon adventure, I’ll admit to bringing along the stereotypical “mom bag” full of snacks, water bottles, and sunscreen. (I’d still recommend those things even if you’re not trekking out with small humans.) I also bring along a camp chair, which can be planted in the creek when I’m tired of walking and ready to sit and read.

What to avoid: Creeking is a pretty open-ended activity; the point is to slow down and watch water striders skitter around (among other natural occurrences). However, I do have to rally against the destructive behavior of making cairns. Stacking rocks may seem benign, but is disruptive to water ecosystems in a multitude of ways. Underwater rocks collect algae and moss, essentially becoming a food farm for countless creatures that dries out when removed from moisture. Rocks also are nesting sites where aquatic species wedge their eggs, and for creatures that live underneath — like crayfish and endangered hellbenders — removing these habitats can cause immense stress. Plus, the practice goes against Leave No Trace principle #4: leave what you find, which encourages us to preserve habitats as we find them for everyone to enjoy.

A note on entering natural bodies of water: While I love jumping in the creek on a hot day, I typically avoid it for about three days after a heavy summer storm. That’s because stormwater runoff enters natural bodies of water, and can temporarily increase the amount of unpleasant bacteria you’re bound to encounter. That’s when having a pool pass may just win out.

🏖

🧺 Foraging Alert: It’s Mulberry Season

Welcome to the start of berry season! Over the next few weeks, strawberries will be reaching their red perfection, gooseberries will ripen, and blackberries will ramp up toward July’s peak production. However, the fruit I’m recommending you seek out this month — the lowly mulberry — takes a little work to get your paws on. There’s no finding these miniature berries in a clamshell package at your local grocer. However, if you’re intrigued by foraging and don’t know where to start, mulberries may be the gateway fruit to your newest hobby.

The U.S. is home to only one native species — the red mulberry (Morus rubra), which flowers in April and May before producing its tiny fruit all summer long. However, mulberries are often overlooked and even considered a nuisance when their tiny fruits rain down on cars and driveways. According to a vintage guide to Missouri trees I recently picked up, it’s really just humans who disregard the value of mulberries:

Since the tree is so small, it has little commercial use. It is very durable, tough, and makes good fence posts. Game species of wildlife and songbirds find it extremely valuable. Turkeys, grouse, squirrels, raccoons, opossums, foxes, and even skunks eat the berries as do scores of songbirds.

Convinced you need to try them out? Great. But more importantly, are you ready to fight some birds for berries? Perfect.

When to hunt: June through August

Spotting mulberry trees this time of year is easy thanks to their distinctive fruit that resemble tiny blackberries, though it helps to look out for their 4” (or larger) oval-ish leaves with sharp points and jagged edges. Check out this guide from Purdue University on identifying mulberries (while it speaks to these trees in Indiana, the reference photos are helpful, and it explains the differences between red and white mulberries, the latter of which is a prolific and edible non-native).

Where to look: Practically everywhere

Mulberry trees are widespread throughout the U.S., planted in parks and found in wooded lowland areas. I’ve even had luck asking around — many people have mulberry trees in their yards and detest how the fruit stains sidewalks and driveways. Taking some of those berries off their hands can work to your benefit.

How to harvest: Shake it like a Polaroid picture

When it comes to harvesting, you’re looking for dark red to purple mulberries. If you’re seeing mostly white or green fruit, chances are you’re a little too early. Ripe mulberries pop off the tree easily, though picking these tiny fruits is tedious. You can make it a little easier by gently shaking the branches to release them onto a sheet or tablecloth below.

Using your mulberry harvest

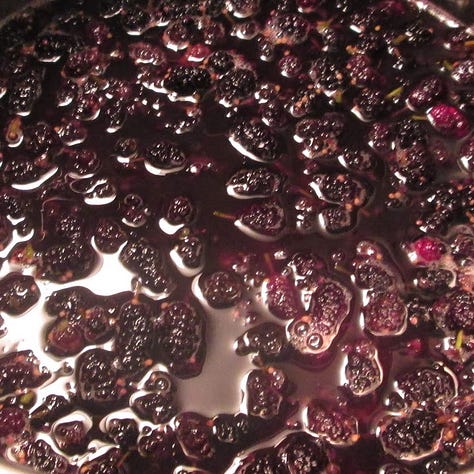

Mulberries are safe to eat straight from the tree, though my personal favorite is turning them into jelly. As a kid, I definitely turned up my nose in favor of the sweeter blackberries and other wild fruits, but a backyard mulberry tree changed my opinion about 8 years ago. At the time, I was high on the thrill of canning, and these very free fruit were just hanging on a huge tree in my backyard. Turns out, the berries I once found too seedy to eat were absolutely divine when squeezed for jelly-making. I’m saying “eat freshly made jelly straight from the pot, skip pouring it in jars” good.

Now that we live in a more urban area, I’ve had less luck finding mulberry trees, but I still look forward to jelly-making. One of my tricks is freezing each small harvest to keep the berries fresh, and defrosting them all when I have enough to work with. When that day arrives, I turn to the same recipe I’ve used for the past 8 years, courtesy of the National Center for Home Food Preservation (one of the best sources out there for canning, dehydrating, and more):

Mulberry Jelly

Ingredients:

3.5 cups of mulberry juice (from about 2 quarts of berries)

¼ cup of lemon juice

1 box of powdered pectin

5 cups of sugar

Makes about six 8-ounce jars of jelly.

Wash your mulberries and remove any that are spoiled or unripe. Heat them slowly in a large pot, mashing them occasionally until the juices begin to flow. Remove from heat and continue mashing, then strain through cheesecloth (really get in there to squeeze out that hard-earned juice). Return the juice and lemon juice to the stove at medium heat, stir in the box of pectin, and get it boiling. Next up, add in the sugar and bring it to a rolling boil for about a minute while stirring constantly (but avoid whisking too vigorously to prevent making foam). When making jelly, I like to keep a plate chilling in the freezer so I can test whether it’s ready — as it cools, finished jelly should take its jiggly shape, while runny jelly needs a bit more cooking time. The trick with warm jelly is working quickly; you want to move it into jars as soon as it’s ready so that sets properly.

From here, I move on to water bath canning my mulberry jelly so that it keeps on the shelf, but you don’t have to. Freshly cooked jellies can last up to a month in the fridge, so long as you don’t devour it all on day one. 🧺

Arrivals, departures, and other nature notes

Get underground during National Cave Week. Geologists are celebrating the awe-inspiring ecosystems of caves and karsts from June 2 through 8, and you can, too. More than 20 U.S. national parks (and NASA) are joining the weeklong celebrations. I ventured out to Wind Cave and Jewel Cave National Parks during my apparent “cave girl summer” in 2023 and can report that even if you’re a little claustrophobic, the chilly 50-degree underground temps are a perfect summertime reprieve. No caves nearby? Several national park sites offer virtual cave tours, like this awesome multi-part tour of Lehman Caves at Great Basin National Park in Nevada.

Everything nice thing you think about lightning bugs is a lie. Dramatic, yes, but hear me out. I originally planned this little brief to be a warm welcome to the flittering jewels of the night sky… but when I got to researching lightning bugs, I learned they may have the best PR manager of all summertime insects. About 200 species of fireflies are scattered throughout North America, best known for their flashing lights that miraculously sync up en masse. But before reaching their beloved flying form, lightning bugs — which are actually beetles — spend months to years underground or in rotting logs as larvae. In this stage, they’re ravenous hunters that thrive on a diet of slugs, grubs, snails, and worms. How do they catch them, you ask? By injecting their prey with a paralyzing neurotoxin, and then using digestive enzymes to break down the carcasses for easy consumption. Really makes you look at those friendly flickering bugs a little differently, doesn’t it?

Ready to fawn over some adorably spotted deer? White-tailed deer fawns are typically born between late May and early June, though it may be a few weeks before you see them. After birth, low-energy fawns spend the first week or so bedding down out of sight and away from their mothers (save for a few nursing visits), a trick does use to avoid attracting predators. As June progresses, fawns move into the “flush phase,” where they still hideout but may run (aka “flush”) if approached and audibly bleat when looking for mom. This is often when well-meaning observers stumble across “abandoned” or “distressed” fawns, though these little cervids are best left alone; chances are, their mothers aren’t far off. By July, fawns have typically gained enough strength to flee danger, which earns them a golden ticket to join the herd and makes viewing them much easier. Fawns tend to lose their adorable white spots around three to four months old in favor of their winter coats, so catch a glimpse while you can.

Groundhog kits are making their entrance, too. I am acutely aware of their arrival, considering I’ve been battling the same garden-destroying groundhog for the past three years. I plant my veggies, she lunches, I attempt to trap her all season, winter arrives and she hibernates, and we start again the next spring. However, this week my nemesis marched three kits into my tomato and pepper beds, and while I’m full of rage about their destructive tendencies, seeing the little chucklings out and about is cuter than expected. In just three short months, these chonky members of the marmot family will set off on their own adventures (which include swimming and climbing trees). In the meantime, I’ll be putting up more fencing and deterrents, and reminding myself of the gardening mantra: “If something isn’t eating your plants, then your garden is not part of the ecosystem.”

Pollinator Week gives you a reason to buy more plants. (Not that you really need one.) June 17-23 honors the critical role pollinators of all types play in our ecosystems, particularly at a time when pollinator species are globally declining. One way to support these hardworking insects — which include the obvious bees and butterflies along with the lesser recognized moths, wasps, beetles, and flies — is the addition of a few native plants to your outdoor living space. I’m currently obsessed with salvias and have planted eight this spring (but who’s counting?) since they’re hardy, maintenance-free, and smell delicious. If you’re intrigued by native plant gardening but don’t know where to start, check out the National Wildlife Federation’s Native Plant Finder tool for region-specific suggestions.

Nature in the news

A few recommendations of things I’ve read, watched, or listened to this month

Read: “Should the Hawthorn Be Saved?” from The Atlantic

Writer and field botanist Robert Langellier’s piece discusses the rise and fall of hawthorn trees, and gives a fascinating insight to how botanists and ecosystems respond when a once-dominant species begins to slip away.

Read: “Interstates Could Be the Highway to Health for Bee Populations in Missouri ” from NPR

Marissanne Lewis-Thompson (one of my favorite St. Louis NPR voices!) details how turning the green spaces in highway medians into miles-long pollinator gardens may be one avenue to boosting regional bee and butterfly populations.

Read: “Hundreds of Starving Brown Pelicans are Turning Up on California Beaches, Puzzling Wildlife Rescuers and Scientists” from Smithsonian Magazine

I originally caught this story on the evening news, captivated by images of veterinarians stuffing fish down pelican gullets. All lightheartedness aside, I’m intrigued as to why these pelicans are starving despite ample food availability, and eager to see what researchers discover.

Shameless plugs for my work around the web

If catching the next big Hollywood hit in theaters is on your bucket list, you might find interest in this piece I wrote last year about the history of summer blockbusters. I’m also looking to expand into a few new publications this summer. Please reach out if you’re an assigning editor looking to add on more outdoor or gardening content!

That’s it for this month’s edition of Outdoor Humans. We’ll chat again in July with a special summer camp-themed edition.

Thanks for reading, but more importantly: go get outside!

Nicole Garner Meeker

Have you subscribed? Get the next issue of Outdoor Humans, released monthly, straight to your inbox.

Another great one! Mulberries were me, , my cousins and of course your Mother's go to for something sweet and free when we were younger. I am a little taken back to hear about the carnivorous habits of the lightening bugs. Lastly, a reminder about creek walks! Best childhood memories all rolled up in one writing.